Dromornithidae

Conservation status: Fossil |

Genyornis newtoni

|

|

Scientific classification |

| Kingdom: |

Animalia

|

| Phylum: |

Chordata

|

| Class: |

Aves

|

| Order: |

Anseriformes

|

| Family: |

Dromornithidae

P. Rich,

1979 |

|

| Genera |

Dromornis

Barawertornis

Bullockornis

Ilbandornis

Genyornis |

Dromornithidae were a

family of large, flightless

birds that lived in

Australia until the end of the

Pleistocene, but are now

extinct. They were long believed to belong to the

order of Struthioniformes, but are now usually classified as

a family of Anseriformes1. Their closest living relatives

are waterfowl such as

ducks and

geese.

The scientific name Dromornithidae derives from

Greek dromaios ("swift-running") and ornis

("bird"). Additionally, the family has been called

Thunder birds, giant emus, giant runners,

demon ducks and Mihirungs. The latter word is

derived from

Chaap Wuurong (Tjapwuring) mihirung paringmal for

a "giant

emu".

The name used in this article, dromornithids, is

derived from the family name.

Including the probably largest bird that ever lived —Dromornis

stirtoni grew up to 3 meters tall— dromornithids were part

of the Australian megafauna. This collective term is used to

describe a number of comparatively large species of animals

that lived in Australia from 20,000 to 50,000 years ago. The

causes for the disappearance of these animals are under

dispute (see "Extinction" below). It is also not clear to

what degree dromornithids were carnivores. The massive,

crushing beaks of some species suggest that at least some

members of the family were a combination of carnivorous

predators and scavengers (much like today's hyenas) or

omnivores. Other features, such as the "hoof-like" feet,

stomach structure, and eye structure that resulted in a wide

field of vision but likely also created a centre blind spot

of about forty degrees (which would hinder hunting

significantly) suggest a more herbivorous, migratory lifestyle.

Appearance

Dromornithids looked superficially like very large

emus

or

moas. Most were heavy-bodied, with powerfully developed

legs and greatly reduced wings. The last bones of the toes

resembled small hooves, rather than claws as in most birds.

Like emus and other flightless birds, dromornithids lost the

keel on the breastbone (or sternum), that serves as the attachment for the large

flight muscles in most

bird skeletons. Their skull also was quite different

from that of emus. These birds ranged from about the size of

a modern

cassowary (1.5 to 1.8 meters) up to 3 meters in the case

of

Dromornis stirtoni, possibly the largest bird that

ever lived.

Species

As of

2005, 5 genera and 7 species have been described, and at

least one new genus is currently under study. The smallest

species was Barawertornis tedfordi, a bird about the size of a

modern

cassowary, weighing 80-95 kg. The two species of

Ilbandornis (Ilbandornis lawsoni and Ilbandornis

woodburnei) were larger birds, but had

more slender legs than the other dromornithids and were

similar to

ostriches in their build and size. Bullockornis planei

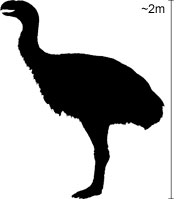

(the Demon Duck of Doom) and Genyornis newtoni (the mihirung)

were more heavily built, stood about 2-2.5m tall and

probably reached weights of 220 to 240 kg. The largest

dromornithids were Dromornis australis and the massive

Dromornis stirtoni (Stirton's Thunderbird).

Distribution

Records of these birds are known only from Australia.

Most of the records of dromornithids come from the eastern

half of the continent, although fossil evidence of has also

been discovered in Tasmania and Western Australia. At some

Northern Territory sites they are very common, sometimes

comprising 60-70% of the fossil material. A fragment of a

dromornithid-sized foot bone has been found in Antarctica, but whether it represents these birds is

uncertain.

Age

The earliest bones identified were found in Late

Oligocene deposits at Riversleigh, northwest Queensland.

There are foot impressions from the Early Eocene in

southeast Queensland that may be referable to dromornithids.

The most recent evidence, of Genyornis newtoni, has been

found at Cuddie Springs, north central New South Wales and dated at 31,000 years old.

Discovery

The most recent species, Genyornis newtoni, was

certainly known to Aborigines during the Late Pleistocene.

Cave paintings thought to depict this bird are known, as are

carved footprints larger than those considered to represent

emus. At Cuddie Springs, Genyornis bones have been

excavated in association with human artifacts. The issue of

how much of an impact humans had on dromornithids and other

large animals of the time is unresolved and much debated.

Many scientists believe that human settlement and hunting

were largely responsible for the extinction of many species

of the

Australian megafauna.

The first Europeans to encounter the bones of

dromornithids may have been Thomas Mitchell and his team.

While exploring the Wellington Caves, one of his men tied

his rope to a projecting object which broke when he tried to

descend down the rope. After the man had climbed back up, it

was found that the projecting object was the fossilised long

bone of a large bird. The first species to be described was

Dromornis australis. The specimen was found in a 55 meter

deep well at Peak Downs, Queensland, and subsequently

described by Richard Owen in 1872.

Extensive collections of any dromornithid fossils were

first made at Lake Callabonna, South Australia.

In

1892, E.C. Stirling and A.H. Zietz of the South Australian

Museum received reports of large bones in a dry lake bed in

the northwest of the state. Over the next years, they made

several trips to the site, collecting nearly complete

skeletons of several individuals. They named the newfound

species Genyornis newtoni in 1896. Additional remains of Genyornis have been

found in other parts of South Australia and in New South

Wales and Victoria.

Other sites of importance were Bullock Creek and Alcoota,

both in the Northern Territory. The specimen recovered there

remained unstudied and unnamed until 1979, when Patricia

Rich described five new species and four new genera. As of

2005, another new genus and species is under study at

the Australian Museum.

Fossils

The best represented bones of dromornithids are

vertebrae, long bones of the hindlimb and toe bones. Ribs

and wing bones are uncommonly preserved. The rarest part of

the skeleton is the skull. For many years, the only skull

known was a damaged specimen of Genyornis. Early

reconstructions of dromornithids made them appear like

oversized emus. Peter Murray and Dirk Megirian, of the

Northern Territory Museum in Australia, recovered enough

skull material of Bullockornis to give a good idea of what

that bird's head looked like. It is now known that

Bullockornis' skull was very large, with the enormous bill

making up about two-thirds of it. The bill was deep, but

rather narrow. The jaws had cutting edges at the front as

well as crushing surfaces at the back. There were

attachments for large muscles, indicating that

Bullockornis had a powerful bite. More fragmentary

remains of the skull of Dromornis suggest that it, too, had

an oversized skull.

Bones are not the only remains of dromornithids that have

been found:

- The polished stones that the birds kept in their

gizzards (muscular stomachs) occur at a number of sites.

These stones, called gastroliths, played an important role in their

digestion by breaking up coarse food or matter that was

swallowed in large chunks.

- Series of footprints, called

trackways, have been found at several sites.

Impressions of the inside of the skull cavity (endocranial

casts o

r endocasts) have been found. Endocasts are

formed when sediments fill the empty skull, after which

the skull is destroyed. These fossils give a fairly

accurate picture of dromornithid brains.

- Almost complete eggs have been found on occasion and

eggshell fragments are common in some areas of sand

dunes.

Diet

It has been generally thought that the dromornithids were

plant eaters. This belief is based on:

- the lack of a hook at the end of the bill

- the lack of talons on the toes

- the association of gizzard stones (caveat:

gastroliths are also found the stomachs of some

carnivores, such as modern crocodiles)

- the large number of individuals occurring together,

suggesting flocking behaviour.

The very large skull and deep bill of Bullockornis,

however, are very unlike those found in large herbivorous

birds such as moas. If this dromornithid ate plants, it was

equipped to process very robust material that has thus far

not been identified. Growing and maintaining such a large

head would be detrimental and probably not occur unless it

provided a substantial benefit of some sort, although it may

have just been a social signal - this, however, would

require a highly developed or complex social structure to

evolve.

It has been suggested that, despite the indications of

herbivory in some dromornithids, Bullockornis may

have been a carnivore or possibly a scavenger. The jaws

could easily cut meat and their robust structure could have

resisted damage if it bit into bones. The bird could easily

have fed on the carcasses of large animals.

It is, of course, not necessary that all dromornithids

had the same diet. There is good evidence that Genyornis,

at least, was a plant eater.

Amino acid analysis of eggshells indicates that this

species was herbivorous. Bullockornis and

Dromornis, with larger heads, may have had different

diets.

Locomotion

Because of their enormous size, dromornithids have been

considered to have been slow lumbering creatures. Their legs

are not long and slender like those of emus or ostriches,

which are specialised for running. However, biomechanical

analysis of the attachments and presumed sizes of the

muscles suggest that dromornithids might have been able to

run much faster than originally thought, making up for their

less then ideal form with brute strength.

Phylogeny

What the nearest relatives of this group are is a

controversial issue. For many years it was thought that

dromornithids were related to

ratites, such as emus, cassowaries and ostriches. It is

now believed that the similarities between these groups are

the result of similar responses to the loss of flight. The

latest idea on dromornithid relationships, based on details

of the skull, is that they evolved early in the lineage that

includes [waterfowl].

Extinction

The reasons for the extinction of this entire family

along with the rest of the Australian megafauna by the end

of the Pleistocene are still debated. It is hypothesized

that the arrival of the first humans in Australia (around

48-60 thousand years ago) and their hunting and

landscape-changing use of fire may have contributed to the

disappearance of the megafauna. However, drought conditions

during peak

glaciation (about 18,000 years ago) are a significantly

confounding factor. Recent studies (Roberts et al. 2001)

appear to rule this out as the primary cause of extinction,

but there is also some dispute about these studies (Wroe et

al. 2002). It is likely that a combination of all of these

factors contributed to the megafauna's demise. However,

there is significant disagreement about the relative

importance of each.

See also

External links

References

- Archer, M. (1999): Brain of the demon duck of doom.

Nature Australia 26(7): 70-71.

- Clarke, W. B. (1877): On Dromornis Australis

(Owen), a new fossil bird of Australia.

Journal of the Proceedings of the Royal Society of New

South Wales 11: 41-49.

- Field, J. H. & Boles, W. E. (1998): Genyornis

newtoni and Dromaius novaehollandiae at

30,000 b.p. in central northern New South Wales.

Alcheringa 22: 177-188.

- Jennings, S. F. (1990): The musculoskeletal anantomy

[sic], locomotion and posture of the dromornithid

Dromornis stirtoni from the Late Miocene Alcoota

Local Fauna. Unpublished Honours Thesis, School of

Biological Sciences, Flinders University of South

Australia.

- Murray, P. F. & Megirian, D. (1998): The skull of

dromornithid birds: anatomical evidence for their

relationship to Anseriformes (Dromornithidae,

Anseriformes). Records of the South Australian Museum

31: 51-97.

- Miller, G. H.; Magee, J. W.; Johnson, B. J.; Fogel,

M. L.; Spooner, N. A.; McCulloch, M. T. & Ayliffe, L. K.

(1999): Pleistocene extinction of Genyornis newtoni:

human impact on Australian megafauna.

Science 283: 205-208.

DOI:10.1126/science.283.5399.205

(HTML abstract)

- Owen, R. (1872): [Untitled]. Proceedings of the

Zoological Society of London 1872: 682-683.

- Pain, S. (2000): The demon duck of doom.

New Scientist 166(2240): 36-39.

- Rich, P. (1979): The Dromornithidae, an extinct

family of large ground birds endemic to Australia.

Bulletin of the Bureau of Mineral Resources, Geology and

Geophysics 184: 1-190.

- Rich, P. (1980): The Australian Dromornithidae: a

group of extinct large ratites. Contributions to

Science, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

330: 93-103.

- Rich, P. (1985): Genyornis newtoni Stirling

and Zietz, 1896. A mihirung. In: Rich, P. V. &

van Tets, G. F. (eds.): Kadimakara: Extinct Vertebrates

of Australia, Pp. 188-194. Pioneer Design Studios,

Lilydale, Victoria.

- Rich, P. & Gill, E. (1976): Possible dromornithid

footprints from Pleistocene dune sands of southern

Victoria, Australia.

Emu 76: 221-223.

- Rich, P. & Green, R. H. (1974): Footprints of birds

at South Mt Cameron, Tasmania.

Emu 74: 245-248.

- Roberts, R. G.; Flannery, T. F.; Ayliffe, L. A.;

Yoshida, H,; Olley, J. M.; Prideaux, G. J.; Laslett, G.

M.; Baynes, A.; Smith, M. A.; Jones, R. & Smith, B. L.

(2001): New ages for the last Australian megafauna:

continent-wide extinction about 46,000 years ago.

Science 292: 1888-1892.

DOI:10.1126/science.1060264

(HTML abstract)

Supplementary Data

Erratum (requires login)

- Stirling, E. C. (1913). Fossil remains of Lake

Callabonna. Part IV. 1. Description of some further

remains of Genyornis newtoni, Stirling and Zietz.

Memoirs of the Royal Society of South Australia

1: 111-126.

- Stirling, E. C. & Zietz, A. H. C. (1896).

Preliminary notes on Genyornis newtoni: a new

genus and species of fossil struthious bird found at

Lake Callabonna, South Australia. Transactions of the

Royal Society of South Australia 20: 171-190.

- Stirling, E. C. & Zietz, A. H. C. (1900). Fossil

remains of Lake Callabonna. I. Genyornis newtoni.

A new genus and species of fossil struthious bird.

Memoirs of the Royal Society of South Australia 1:

41-80.

- Stirling, E. C. & Zietz, A. H. C. (1905). Fossil

remains of Lake Callabonna. Part III. Description of the

vertebrae of Genyornis newtoni. Memoirs of the

Royal Society of South Australia 1: 81-110.

- Vickers-Rich, P. & Molnar, R. E. (1996). The foot of

a bird from the Eocene Redbank Plains Formation of

Queensland, Australia. Alcheringa 20:

21-29.

- Williams, D. L. G. (1981). Genyornis eggshell

(Dromornithidae; Aves) from the Late Pleistocene of

South Australia. Alcheringa 5: 133-140.

- Williams, D. L. G. & Vickers-Rich, P. (1992). Giant

fossil egg fragment from the Tertiary of Australia.

Contributions to Science, Natural History Museum of Los

Angeles County 36:

375-378.

- Wroe, S. (1999): The bird from hell? Nature

Australia 26(7): 56-63.

- Wroe, S.; Field, J. & Fullagar, R. (2002): Lost

giants. Nature Australia 27(5): 54-61.