|

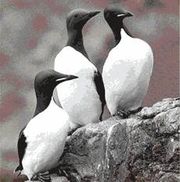

Auks |

Parakeet Auklets

|

|

Scientific classification |

| Kingdom: |

Animalia

|

| Phylum: |

Chordata

|

| Class: |

Aves

|

| Order: |

Charadriiformes

|

| Family: |

Alcidae

Leach, 1820 |

|

|

Genera |

Uria

Alle

Alca

Pinguinus

Synthliboramphus

Cepphus

Brachyramphus

Ptychoramphus

Aethia

Cerorhinca

Fratercula

Extinct Genera, see

Systematics |

- This article is about a family of birds. For the

American ornithological journal, see

The Auk.

Auks are

birds of the family Alcidae in the order

Charadriiformes. They are superficially similar to

penguins due to their black-and-white colours, their

upright posture and some of their habits. Nevertheless they

are not related to the penguins at all, but considered by

some to be a product of moderate

convergent evolution.

In contrast to penguins, the modern auks are able to fly

(with the exception of the recently extinct

Great Auk). They are good swimmers and divers, but their

walking appears clumsy. Due to their short wings auks have

to flap their wings very fast in order to fly.

Auks live on the open sea and only go ashore for

breeding, although some species, like the

Common Guillemot, spend a great part of the year

defending their nesting spot from others.

Several species have different names in

Europe and North America. The guillemots of Europe are murres in

North America, if they occur in both continents, and the

Little Auk becomes the Dovekie.

Some species, such as the Uria guillemots, nest in large

colonies on cliff edges; others, like the

Cepphus guillemots, breed in small groups on rocky

coasts; and the

puffins, auklets and some murrelets nest in burrows. All

species except the

Brachyramphus murrelets are colonial.

Evolution and distribution

Traditionally, the auks were believed to be one of the

earliest distinct charadriiform lineages due to their

characteristic morphology. However, molecular analyses have

demonstrated that these peculiarities are the product of

strong natural selection instead: as opposed to, for

example, plovers (a much older charadriiform lineage), auks

radically changed from a wading shorebird to a diving

seabird lifestyle. Thus, today, the auks are no longer

separated in their own suborder ("Alcae"), but are

considered part of the Lari suborder which otherwise

contains gulls and similar birds. Judging from molecular

data, their closest living relatives appear to be the skuas,

with these two lineages separating about 30 MYA (Paton et

al., 2003). This may or may not be correct due to

uncertainties of the fossil record (Thomas et al., 2004, and

see below). Alternatively, auks may have split off far

earlier from the rest of the Lari and undergone strong

morphological, but slow molecular evolution, which would

require a very high evolutionary pressure, coupled with a long lifespan and

slow reproduction.

The earliest unequivocal fossils of auks are from the

Miocene (e.g. the genus Miocepphus, 15 MYA). Two very

fragmentary fossils are often assigned to the Alcidae,

although this may not be correct: Hydrotherikornis (Late

Eocene, some 35 MYA) and Petralca (Late Oligocene). Most

extant genera are known to exist since the Late Miocene or

Early Pliocene (c. 5 MYA). Miocene fossils have been found

in both California and Maryland, but the greater diversity

of fossils and tribes in the Pacific leads most scientists

to conclude that it was there they first evolved, and it is

in the Miocene Pacific that the first fossils of extant

genera are found. Early movement between the Pacific and the

Atlantic probably happened to the south (since there was no

northern opening to the Atlantic), later movements across

the Arctic Sea (Konyukhov, 2002). The flightless subfamily

Mancallinae which was apparently restricted to the Pacific

coast of southern North America became extinct in the Early

Pleistocene.

The extant auks (subfamily Alcinae) are broken up into 2

main groups: the usually high-billed puffins (tribe

Fraterculini) and auklets (tribe Aethiini), and the more

slender-billed murres (tribe Alcini) and the murrelets and

guillemots (tribes Brachyramphini and Cepphini). Molecular

studies (Friesen et al., 1996; Moum et al.,

2002) confirm this arrangement except that the

Synthliboramphus murrelets should be split into a

distinct tribe, as they appear more closely related to the

Alcini.

Compared to other families of seabirds, there are no

genera with many

species (such as the 47

Larus

gulls). This is probably a product of the rather small

geographic range of the family (the most limited of any

seabird family), and the periods of

glacial advance and retreat that have kept the

populations on the move in a narrow band of subarctic ocean.

Razorbills are only found in the Atlantic Ocean

Today, as in the past, the auks are restricted to cooler

northern waters. Their ability to spread further south is

restricted as their prey hunting method, pursuit diving,

becomes less efficient in warmer waters. The speed at which

small fish (which along with krill are the auk's principal

food items) can swim doubles as the temperature increases

from 5°C to 15°C, with no corresponding increase in speed

for the bird. The southernmost auks, in California and

Mexico, can survive there because of cold upwellings. The

current paucity of auks in the Atlantic (6 species),

compared to the Pacific (19-20 species) is considered to be

because of extinctions to the Atlantic auks; the fossil

record shows there were many more species in the Atlantic

during the Pliocene. Auks also tend to be restricted to

continental shelf waters and breed on few oceanic islands.

Feeding and ecology

The feeding behaviour of auks is often compared to that

of

penguins; they are both

wing-propelled pursuit divers. In the region where auks

live their only seabird competition is with

cormorants (which dive powered by their strong feet); in

areas where the two groups feed on the same prey the auks

tend to feed further offshore.

Although not to the extent of penguins, auks have to a

large extent sacrificed flight, and also mobility on land,

in exchange for swimming; their wings are a compromise

between the best possible design for diving and the bare

minimum needed for flying. This varies by subfamily, the

Uria guillemots (including the

Razorbill) and murrelets being the most efficient under

the water, whereas the puffins and auklets are better

adapted for flying and walking. This reflects the type of

prey taken; murres hunt faster schooling fish, whereas

auklets take slower moving krill. Time depth recorders on

auks have shown that they can dive as deep as 100 m in the

case of Uria guillemots, 40 m for the Cepphus

guillemots and between 30 m for the auklets.

Social behaviour and breeding

Marbled Murrelets breed singly and have brown

breed plumage to blend into their nesting sites.

The majority of auk species are

colonial, nesting in anything between small groups to large

thousand strong colonies. As well as possible advantages for

defence against predators, there is a benefit in terms of

foraging to being colonial; birds that see a neighbour

returning with food will set off to forage in the direction

it came from. Two species, the Marbled Murrelet and the

Kittlitz's Murrelet are solitary nesters, choosing old

growth forest and high mountains respectively. In these

areas the benefits of colonial nesting would be outweighed

by the presence of terrestrial predators (foxes and

raccoons, for example) which island and cliff breeding

auks do not have to deal with.

Nesting sites in colonies can vary from nothing more than

a patch on a cliff face, to natural crevices in the rocks

and boulders, to burrows dug by the bird. Many nesting sites

are attended nocturnally, in some cases as the adults are

likely to fall victim to kleptoparasitism (such as the

Rhinoceros Auklet) or because the adults themselves are

likely prey items (like the Cassin's Auklet). Mating itself

can happen both on the colony, as happens with the Razorbill

and Little Auk, or at sea, as is the case for

puffins and auklets.

Systematics

Common (centre) and Brunnich's Guillemots

Black Guillemot in summer and winter

plumages

ORDER

CHARADRIIFORMES

Suborder

Lari

Family Alcidae

-

Hydrotherikornis (fossil,

disputed)

- Subfamily Petralcinae (fossil,

disputed)

- Subfamily Alcinae

-

Miocepphus (fossil)

- Tribe Alcini - Auks and murres

-

Uria

-

Common Guillemot or Common Murre,

Uria aalge

-

Brunnich's Guillemot or Thick-billed

Murre, Uria lomvia

-

Little Auk or Dovekie, Alle alle

-

Great Auk, Pinguinus impennis (extinct,

c.1844)

-

Razorbill, Alca torda

- Tribe Synthliboramphini -

Synthliboramphine murrelets

-

Synthliboramphus

-

Xantus's Murrelet, Synthliboramphus

hypoleucus - sometimes separated in

Endomychura

-

Craveri's Murrelet, Synthliboramphus

craveri - sometimes separated in

Endomychura

-

Ancient Murrelet, Synthliboramphus

antiquus

-

Japanese Murrelet, Synthliboramphus

wumizusume

- Tribe Cepphini - True guillemots

-

Cepphus

-

Black Guillemot or Tystie, Cepphus

grylle

-

Pigeon Guillemot, Cepphus columba

-

Kurile Guillemot, Cepphus

(columba) snowi

-

Spectacled Guillemot, Cepphus carbo

- Tribe Brachyramphini - Brachyramphine

murrelets

-

Brachyramphus

-

Marbled Murrelet, Brachyramphus

marmoratus

-

Long-billed Murrelet

Brachyramphus (marmoratus) perdix

-

Kittlitz's Murrelet, Brachyramphus

brevirostris

- Tribe Aethiini - Auklets

-

Cassin's Auklet, Ptychoramphus aleuticus

-

Aethia

-

Parakeet Auklet, Aethia psittacula

-

Crested Auklet, Aethia cristatella

-

Whiskered Auklet, Aethia pygmaea

-

Least Auklet, Aethia pusilla

- Tribe Fraterculini - Puffins

-

Rhinoceros Auklet, Cerorhinca monocerata

-

Fratercula

-

Atlantic Puffin, Fratercula arctica

-

Horned Puffin, Fratercula corniculata

-

Tufted Puffin, Fratercula cirrhata

Biodiversity of auks seems to have been markedly higher

during the

Pliocene (Konyukhov, 2002). See the genus accounts for

prehistoric species.

References

- Collinson, Martin (2006): Splitting

headaches? Recent taxonomic changes affecting the

British and Western Palaearctic lists.

Brit. Birds 99(6): 306-323.

HTML abstract

- Friesen, V. L.; Baker, A. J. & Piatt, J. F.

(1996): Phylogenetic Relationships Within the Alcidae

(Charadriiformes: Aves) Inferred from Total Molecular

Evidence. Molecular Biology and Evolution 13(2):

359-367.

PDF fulltext

- Gaston, Anthony & Jones, Ian (1998):

The Auks, Alcidae. Oxford University Press,

Oxford.

ISBN 0-19-854032-9

- Konyukhov, N. B. (2002): Possible Ways of

Spreading and Evolution of Alcids. Izvestiya Akademii

Nauk, Seriya Biologicheskaya 5: 552–560

[Russian version]; Biology Bulletin 29(5):

447–454 [English version].

DOI:10.1023/A:1020457508769

(Biology Bulletin HTML abstract)

- Moum, Truls; Arnason, Ulfur & Árnason, Einar

(2002): Mitochondrial DNA Sequence Evolution and

Phylogeny of the Atlantic Alcidae, Including the Extinct

Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis). Molecular

Biology and Evolution 19(9): 1434–1439.

PDF fulltext

- Paton, T. A.; Baker, A. J.; Groth, J. G. &

Barrowclough, G. F. (2003): RAG-1 sequences resolve

phylogenetic relationships within charadriiform birds.

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 29:

268-278.

DOI:10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00098-8

(HTML abstract)