|

Hummingbird |

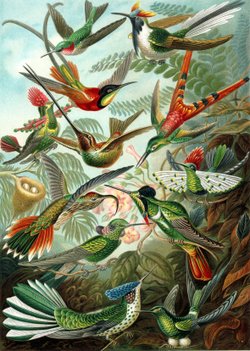

A variety of hummingbirds from

Ernst Haeckel's 1904 Kunstformen der Natur (Artforms of

Nature)

|

|

Scientific classification |

| Kingdom: |

Animalia

|

| Phylum: |

Chordata

|

| Class: |

Aves

|

| Order: |

Apodiformes

|

| Family: |

Trochilidae

Vigors, 1825 |

|

| Subfamilies |

Phaethornithinae

Trochilinae |

Hummingbirds are small

birds in the

family Trochilidae. They are known for their

ability to hover in mid-air by rapidly flapping their

wings, 15 to 80 times per second (depending on the

species). Capable of sustained hovering, the hummingbird has

the ability to fly deliberately backwards or vertically, and

to maintain position while drinking from flower blossoms.

They are named for the characteristic

hum

made by their wings.

Hummingbirds are attracted to many flowering

plants—shrimp plants, Heliconia, bromeliads, verbenas,

fuchsias, many penstemons—especially those with red flowers.

They feed on the nectar of these plants and are important

pollinators, especially of deep-throated flowers. Most

species of hummingbird also take insects, especially when feeding young.

The

Bee Hummingbird (Mellisuga helenae) is the smallest bird in

the world, weighing 1.8 grams. A more typical hummingbird, such as the Rufous

Hummingbird (Selasphorus rufus), weighs approximately

3 g and has a length of 10-12 cm (3.5-4 inches). The largest

hummingbird is the Giant Hummingbird (Patagona gigas),

with some individuals weighing as much as 24 grams.

Most male hummingbirds take no part in nesting. Most

species make a neatly woven cup in a tree branch. Two white

eggs are laid, which despite being the smallest of all bird

eggs, are in fact large relative to the hummingbird's adult

size.

Incubation is typically 14-19 days.

Appearance

Hummingbirds bear the most glittering

plumage and some of the most elegant adornments in the

bird world. Male hummingbirds are usually brightly coloured.

The females of most species are duller.

The names that admiring naturalists have given to

hummingbirds suggest exquisite, fairylike grace and gemlike

brilliance. Fiery-tailed Awlbill, Ruby-topaz Hummingbird,

Glittering-bellied Emerald, Brazilian Ruby, Green-crowned

Brilliant, Festive Coquette, Shining Sunbeam, and

Amethyst-throated Sunangel are some of the names applied

to birds in this group.

Aerodynamics of hummingbird flight

A male

Ruby-throated Hummingbird

Hummingbird flight has been studied intensively from an

aerodynamic perspective: Hovering hummingbirds may be filmed

using high-speed video cameras.

Writing in Nature, biophysicist Douglas Warrick and

coworkers studied the Rufous Hummingbird, Selasphorus rufus,

in a wind tunnel using particle image velocimetry techniques and investigated

the lift generated on the bird's upstroke and downstroke.

They concluded that their subjects produced 75% of their

weight support during the downstroke and 25% during the

upstroke: many earlier studies had assumed (implicitly or

explicitly) that lift was generated equally during the two

phases of the wingbeat cycle. This finding shows that

hummingbirds' hovering is similar to, but distinct from,

that of hovering insects such as the hawk moths. The differences result from an inherently

dissimilar avian body plan (Warrick et al., 2005).

Metabolism

With the exception of insects, hummingbirds while in

flight have the highest metabolism of all animals, a

necessity in order to support the rapid beating of their

wings. Their heartbeat can reach as high as 1260 beats per

minute, a rate once measured in a Blue-throated hummingbird

[1]. They also typically consume more than their own weight

in food each day, and to do that they have to visit hundreds

of flowers daily. At any given moment, they are only hours

away from starving. However, they are capable of slowing

down their metabolism at night, or any other time food is

not readily available. They enter a hibernation-like state

known as torpor. During torpor, the heartrate and rate of

breathing are both slowed dramatically (the heartrate to

roughly 50-180 beats per minute), reducing their need for

food.

Studies of hummingbirds' metabolism are highly relevant

to the question of whether a

migrating

Ruby-throated Hummingbird can cross 800 km (500 miles) of

the Gulf of Mexico on a nonstop flight, as field

observations suggest it does. This hummingbird, like other

birds preparing to migrate, stores up fat to serve as fuel,

thereby augmenting its weight by as much as 40 to 50 percent

and hence increasing the bird's potential flying time.

(Skutch, 1973)

Range

Hummingbird nest with two chicks in Santa

Monica, CA

Hummingbirds are found only in the Americas, from

southern Alaska and Canada to Tierra del Fuego, including

the West Indies. The majority of species occur in tropical

Central and South America, but several species also breed in

temperate areas. Excluding vagrants, sometimes from Cuba or

the Bahamas, only the migratory Ruby-throated Hummingbird

breeds in eastern North America. The Black-chinned

Hummingbird, its close relative and another migrant, is the

most widespread and common species in the western United

States and Canada.

Most hummingbirds of the U.S. and Canada and southern

migrate to warmer climates in the northern winter, though

some remain in the warmest coastal regions. Some southern

South American forms also move to the tropics.

The Rufous Hummingbird shows an increasing trend to

migrate east to winter in the eastern United States, rather

than south to Central America, as a result of increasing

survival prospects provided by artificial feeders in

gardens. In the past, individuals that migrated east would

usually die, but now many survive, and their changed

migration direction is inherited by their offspring.

Provided sufficient food and shelter is available, they are

surprisingly hardy, able to tolerate temperatures down to at

least -20°C.

Systematics and evolution

A male

Costa's Hummingbird, showing its plumage to

good effect

Traditionally, hummingbirds were placed in the order

Apodiformes, which also contains the

swifts. In the

Sibley-Ahlquist taxonomy, hummingbirds are separated as

a new order, Trochiliformes, but this is not well supported

by additional evidence.

There are between 325 and 340 species of hummingbird,

depending on taxonomic viewpoint, divided into two

subfamilies, the

hermits (subfamily Phaethornithinae, 34

species in six genera), and the typical hummingbirds

(subfamily Trochilinae, all the others). This

arrangement has been extensively verified (see review in

Gerwin & Zink, 1998).

The modern diversity of hummingbirds is thought by

evolutionary biologists to have evolved in South America, as

the great majority of the species are found there. All of

the most common North American species are thought to be of

relatively recent origin, and are therefore (following the

usual procedure of lists starting with more 'ancestral'

species and ending with the most recent) listed close to the

end of the list. However, as seen below, the actual origin

of the hummingbird lineage now seems to have been parts of

Europe to what is southern

Russia today.

Genetic analysis has indicated that the hummingbird

lineage diverged from their closest relatives some 35

million years ago, in the Late

Eocene, but fossil evidence has proved quite elusive. Fossil

hummingbirds are known from the Pleistocene of Brazil and

the Bahamas - neither of which has been scientifically

described -, and there are fossils and subfossils of a few

extant species known, but until recently, older fossils had

not been securely identifiable as hummingbirds.

Then, in

2004, Dr. Gerald Mayr of the Senckenberg Museum in Frankfurt

am Main identified two 30-million-year-old hummingbird

fossils and published his results in Nature. The fossils of

this primitive hummingbird species, named Eurotrochilus

inexpectatus ("unexpected European hummingbird"), had been

sitting in a museum drawer in Stuttgart; they had been

unearthed in a clay pit at Wiesloch-Frauenweiler, south of

Heidelberg, Germany and because it was assumed that hummingbirds

never occurred outside the Americas were never believed to

be hummingbirds until Mayr took a closer look at them.

Fossils of birds not clearly assignable to either

hummingbirds or a related, extinct family, the

Jungornithidae, have been found at the Messel pit and in the

Caucasus, dating from 40-35 mya, proving that the split

between these two lineages indeed occurred at that date. The

areas where these early fossils have been found had a

climate quite similar to the northern Caribbean or

southernmost China during that time. The biggest remaining

mystery at the present time is what happened to hummingbirds

in the roughly 25 million years between the primitive

Eurotrochilus and the modern fossils. The astounding

morphological adaptations, the decrease in size and the

dispersal to the Americas and extinction in Eurasia all

occurred during in this timespan. DNA-DNA hybridization

results (Bleiweiss et al, 1994) suggest that the main

radiation of South American hummingbirds at least partly

took place in the Miocene, some 12-13 mya, durng the uplifting of the

northern

Andes.

Hummingbirds and humans

A female Ruby-throated Hummingbird in flight;

note the speed of the wingbeats

Hummingbirds sometimes fly into

garages and become trapped. It is widely believed that this

is because they mistake the hanging (usually red-color)

door-release handle for a flower, although hummingbirds can

also get trapped in enclosures that do not contain anything

red. Once inside, they may be unable to escape because their

natural instinct when threatened or trapped is to fly upward.

This is a life-threatening situation for hummingbirds, as

they can become exhausted and die in a relatively short

period of time, possibly as little as an hour. If a trapped

hummingbird is within reach, it can often be caught gently

and released outdoors. It will lie quietly in the space

between cupped hands until released.

Hummingbird feeders and nectar

The diet of hummingbirds requires an energy source

(typically

nectar) and a protein source (typically small insects). For

nectar, hummingbirds will happily take artificial nectar

from man-made feeders. Such feeders allow people to observe

and enjoy hummingbirds up-close while providing the

hummingbirds with a reliable supply of nectar, especially

when flower blossoms are less abundant.The feeders can be

placed as high as 60 meters maximum. Homemade nectar can be

made from 1 part white, granulated table sugar to

4 parts water, boiled to make it easier to dissolve the

sugar and to purify the solution so that it will stay fresh

longer. The cooled nectar is then poured into the feeder.

Honey should not be used because it is prone to culture a

bacterium that is dangerous to hummingbirds.[1]

Diet sweeteners should also be avoided because, though the

hummingbirds will drink it, they will be starved of the

calories they need to sustain their metabolism.

Some commercial hummingbird foods contain red dyes and

preservatives which are unnecessary and have not been

studied for long-term effects on hummingbirds. While it is

true that bright colors (especially red) attract

hummingbirds, it is better to use a feeder that has some red

on it, rather than coloring the water. There are suggestions

that red dye is harmful to hummingbirds

[2] . Yellow dyes also cannot be used, as it has

been known to attract bees and wasps. Commercial nectar

mixes may contain small amounts of mineral nutrients which

are useful to hummingbirds, but hummingbirds get all

the nutrients they need from the insects they eat, not from

nectar, so the added nutrients are also unnecessary.

Authorities on hummingbirds recommend just plain sugar and

water (Shackelford et al., 2005).

A hummingbird feeder should be easy to refill and clean.

Prepared nectar can be refrigerated for 1 to 2 weeks before

being used, but once placed outdoors it will only remain

fresh for 2-4 days in hot weather or 4-6 days in moderate

weather before turning cloudy or developing mold.

Hummingbirds can be seriously harmed if they sip from a

feeder with nectar that has gone bad. When changing the

nectar, the feeder should be rinsed thoroughly with warm tap

water, flushing the reservoir and ports to remove any

contamination or sugar build-up. If dish soap is used, it

needs extra rinsing so that no residue is left behind. The

feeder can be soaked in dilute chlorine bleach if black

specks of mold appear.

Other animals are also attracted to hummingbird feeders.

It is a good idea to get a feeder that has very narrow

ports, or ports with mesh-like "wasp guards", to prevent

bees and wasps from getting inside where they get trapped.

Orioles are known to drink from hummingbird feeders,

sometimes tipping them and draining the liquid. If this

becomes a problem, it is possible to buy feeders which are

specifically designed to support their extra weight and

which hummingbirds will use too. If ants find your

hummingbird feeder, one solution is to install an "ant

moat", which is available at specialty garden stores and

online.

Hummingbird image at Nazca

Hummingbirds in myth and culture

- The Aztec god Huitzilopochtli is often depicted as a

hummingbird.

One of the Nazca Lines depicts a hummingbird.

The Ohlone tells the story of how a Hummingbird brought

fire to the world. See an article at the National Parks

Conservation Association's website for a recounting.

Trinidad and Tobago is known as "The land of the

hummingbird," and a hummingbird can be seen on that

nation's 1 cent coin.

Many popular songs have been written under the title

"Hummingbird", including separate works by B.B. King,

Wilco, Leon Russell, John Mayer, Frankie Laine, Cat

Stevens, Seals and Crofts, Merzbow and Yuki.

References

Male

Green Violet-ear in flight

- Bleiweiss, Robert; Kirsch, John A. W. &

Matheus, Juan Carlos (1999): DNA-DNA hybridization

evidence for subfamily structure among hummingbirds.

Auk 111(1): 8-19.

PDF fulltext

- del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A. & Sargatal, J.

(editors) (1999):

Handbook of Birds of the World, Volume 5: Barn-owls

to Hummingbirds. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

ISBN 84-87334-25-3

- Gerwin, John A. & Zink, Robert M.

(1998): Phylogenetic patterns in the Trochilidae.

Auk 115(1): 105-118.

PDF fulltext

- Meyer de Schauensee, Rodolphe (1970): A

Guide to Birds of South America. Livingston,

Wynnewood, PA.

- Shackelford, Clifford Eugene; Lindsay, Madge

M. & Klym, C. Mark (2005): Hummingbirds of Texas with

their New Mexico and Arizona ranges. Texas A&M

University Press, College Station.

ISBN 1-58544-433-2

- Skutch, Alexander F. & Singer, Arthur

B. (1973): The Life of the Hummingbird. Crown

Publishers, New York.

ISBN 0-517-50572X

- Warrick, D. R.; Tobalske, B.W. & Powers, D.R.

(2005): Aerodynamics of the hovering hummingbird.

Nature 435: 1094-1097

DOI:10.1038/nature03647

(HTML abstract)

Footnotes

- ^

http://faq.gardenweb.com/faq/lists/hummingbird/2003021845028716.html

- ^

http://www.hummingbirds.net/dye.html

External links

A

Rufous Hummingbird hovering in flight at Hells

Gate, British Columbia