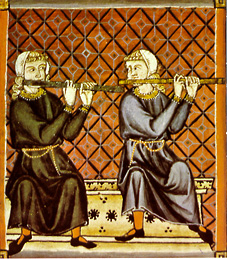

Az európai középkor zenéjébe vélhetően Közép-Ázsiából kerülhetett, az viszont tény, hogy a 13. században már a harántfuvola is, és az egyenes irányban fújt csőrős fuvola, azaz a furulya is ismert volt. A harántfuvolák ebben az időben elsősorban katonai hangszerként, dobok kíséretében szerepeltek, a kifinomultabb zenei ízlés ekkoriban és később, a reneszánszban is inkább az egyenes fuvolát, a furulyát preferálta. A barokk zenében szintén a furulyának volt nagyobb tekintélye, Johann Sebastian Bach fuvolaszólamait is nagyobb részben ilyen hangszerre, kevésbé a maihoz hasonló harántfuvolára írta.

A 17. században a harántsípok két típusa különült el, a katonai célra használt változat (Querpfeife, fifre) és a tulajdonképpeni harántfuvola (Querflöte, fluste d'Allemand). Ez utóbbi 3-4 féle hangfekvésben készült, anyaga leggyakrabban szilvafa vagy buxus, de hegyikristályból, üvegből, később elefántcsontból, ébenfából, ezüstből is készítették.

Kb. 1650-ig a fuvolát egy darabból, hengeres furattal építették hat hanglyukkal. Ekkor jelent meg a több darabból összerakható hangszertípus, melynek csak fejrésze volt hengeres, a testének többi része kúpszerűen szűkülő furattal rendelkezett. A részekből álló hangszer méretezése pontosabb lehetett, darabjainak teleszkópszerű tologatása a tisztább behangolást segítette elő. Ezzel egyidőben kezdtek egyes hangokat billentyűk hozzáadásával elérhetővé tenni. Az új konstrukciójú hangszer kifejlesztésében, népszerűsítésében nagy szerepe volt Johann Joachim Quantz (1697-1773) fuvolavirtuóznak, II. Frigyes porosz király zenemesterének. E módosítások révén a 18. században a harántfuvola fokozatosan átvette riválisa, a furulya helyét, nagyon népszerű hangszerré vált, de továbbra is sok kritika érte hamissága miatt.

A fuvola ma ismert formájának kialakítása - több más fúvós hangszeré mellett - Theobald Böhm (1794-1881) fuvolaművész és aranyműves nevéhez fűződik. 1832-ben készült hangszerén a hanglyukak helyét és átmérőjét nem az emberi kéz anatómiájához igazította, hanem akusztikai megfontolások alapján határozta meg. Minden félhanghoz egymástól azonos távolságra lévő külön hanglyukat rendelt, melyeket gyűrűs billentyűk segítségével fedett. 1847-ben a kúpszerű furat helyett hengeres fémtestet alkalmazott 15 lyukkal és 23 billentyűvel. Ezekkel az újításokkal sikerült kijavítania a hangszer régi hiányosságait, hamisságát, kiegyenlítetlen hangzását, a játéktechnikai nehézségeket. Azóta a fuvola konstrukciója, méretezése alig változott.

A fuvola története évszázadokban

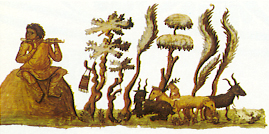

The earliest depictions of a transverse flute in Western culture come from Byzantium in the 10th century.

Nothing is known about what flutes were like, or what music they played, in the 10th century. Pictures provide the only indications that transverse flutes even existed in Europe.

The transverse flute seems to have been unknown in Europe until it arrived from the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire in the Middle Ages. Because it first became known in German lands, it acquired the name "German flute" to distinguish it from other types of flute (such as recorders) that are held vertically. It appears in pictures and poetry beginning in the 12th century, and seems to have been used in courtly music in 13th-century Germany along with harp, fiddle, and rote. A century later it appears as an outdoor military instrument with bells, drums, bagpipes and trumpets.

We know nothing definite about the construction, repertoire, or playing technique of the instrument in these early times. Most pictures show an instrument proportioned like the north Indian bansuri, a bamboo flute with a relatively wide bore in relation to its length, but certainly no standard form existed. It is not certain how or whether instruments and voices performed together, as in the picture at left. The period had no concept of harmony, but its music is based on the concept of modes.

Tenth- and 11th-century Byzantine manuscript illustrations provide hundreds of images of flutes, usually in the hands of shepherds and most often held to the player's right.

Between about 1050 and 1200 the troubadors appeared at the courts of Provence together with their most favoured instrument, the fiddle.

The main instruments for performing art music in the early middle ages were bowed and plucked strings: fiddle, rebec, harp, psaltery, and gittern. The transverse flute appears only occasionally along with other instruments such as portative organ and hurdy-gurdy. It seems to have been known only in the Holy Roman Empire, or the lands loosely known as Germany. This is probably the source of the names flute d'Allemagne and 'German flute' for the transverse instrument.

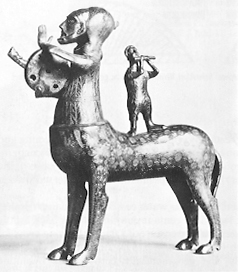

Music was not conceived for specific instruments in this period, and most written references to flutes can refer to duct flutes such as recorders or tabor pipes. Flutes of all kinds are often identified with mythical or spiritual figures, with pastoral life, and with death.

Psalters, the most common books of the middle ages, often contained elaborately decorated page borders and initial capitals showing scenes and figures from daily life. But only two such 12th-century illustrations of transverse flutes have been found.

A transverse flute is shown in an ensemble with harp, fiddle, and rote in an illustration in Rudolf von Ems's Weltchronik (c1255-70). The same combination of instruments occurs in Ulrich von Türheim's Der starke Rennewart (c1300), so perhaps such an ensemble really existed in Austrian and Bavarian aristocratic circles in the 13th century.

A French literary set-piece, Cleomadés (c1285), by Adenet le Roi, lists the musical instruments owned by a famous minstrel. Adenet, himself the chief minstrel at the court of Gui de Damperre, Count of Flanders, gives the first unmistakable literary reference to transverse flutes, as Flahutes d'argent traversaines, or, literally 'silver transverse flutes'.

Fourteenth-century pictures and literary references in France and Germany compare the sound of the flute to the trombone and trumpet. Pictures show transverse flutes being played outdoors by soldiers together with large bells, drums, bagpipes and trumpets.

Transverse flutes appear rather frequently in the hands of angels in illuminated manuscripts made in Bourges and Paris around the turn of the 15th century. But they seem to have remained familiar only in Germany and France, while unknown in other countries such as Italy.

The poet/composer Guillaume de Machaut made a distinction between transverse flutes and recorders or other duct flutes, and Eustache Deschamps suggested that the flute led a double life as a soft, indoor instrument, as well as a loud one with military connotations.

Pictures and literary references involving transverse flutes become rare for about 70 years after the second decade of the 15th century. Most of the references that do exist might refer to duct flutes.

At the end of the 15th century the military flute becomes common again, particularly in the hands of Swiss mercenary troops and in combination with side drums. The flute and drum combinations quickly spread to Italy, France, the German lands, Spain, and Sweden together with new Swiss infantry techniques.

References in the great German saga, the Niebelungenlied (c1300) compare the flute's sound to the trombone and trumpet, while some fourteenth-century pictures of flute-playing indicate that it was used as a military instrument, in combination with large bells, drums, bagpipes and trumpets.

Flutes came into widespread military use after Swiss infantry defeated the supposedly invincible heavy Burgundian cavalry in battles in 1476. The Swiss soldiers used a flute and a drum to signal precise movements to a tight annd mobile formation of soldiers armed with pikes, halberds, swords, crossbows, and firearms. These effective techniques, including the use of the flute, were copied all over Europe within a few years.

No distinction was made at this time between 'flute' and 'fife', so that the earliest written instructions for playing the instrument (Virdung, 1511) described only the instrument's military role. A slightly later instruction book (Agricola, 1529, 1545) showed that by then it was used in four-part consort music too.

The instrument we recognise as a 'fife', a short, shrill flute with six or more fingerholes, had appeared by the end of the 16th century. German mercenary troops and others made it the traditional signalling and ceremonial instrument, so that massed bands of fife and drum became an emblem of the American War of Independence, among other struggles.

The fife was replaced by the bugle in the 19th century, but has recently been revived in Switzerland, by North American war reenactors, and in the Pope's Swiss Guard at the Vatican, which was founded in 1548 but replaced fifes with bugles in 1814.

Pierre Attaingnant publishes two collections containing 58 Chansons in four parts (1533) in Paris. He designates some as suitable for flutes, some for recorders, and some for both. More commonly, publications leave the choice of instruments to the players.

Mixed consorts including flutes first appear in sacred compositions at the Bavarian court in Munich under Orlando di Lasso's direction. Munich musicians soon take these ideas to Venice.

The first printed solo pieces for transverse flute survive from the end of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th. Aurelio Virgiliano's Il Dolcimelo, book 2 (c1600) contains Ricercate in the Italian division style for cornetto, violin, traversa or other instruments.

The flute was made in several sizes in the 16th century. The consort consisted of three sizes of instrument pitched a 5th apart: a bass with a lowest note of G, a tenor/alto with a lowest note of D, and a discant with a lowest note of A. The commonest consort had a bass and three tenor/altos .By the early 16th century, ensembles of flutes had become a favorite for playing the 4-part consort repertoire of that period. Courts in England, Hungary, Madrid, and Stuttgart each owned dozens or even hundreds of transverse flutes.

The flute became much better-known all over Europe in the 14th century as Swiss mercenaries, who used it for marching and signalling, spread its use along with their new infantry techniques. Military flutes are on another page.

In art music of the renaissance the flute, like other instruments, was most commonly used in sets of different-sized family members to play consort music, usually in four parts. In the picture at left (1619) these are shown in the bottom right corner. The music often had to be transposed to fit on a consort of flutes: musicians used the idea of hexachords to make transposing and fingering the different sizes of flute easy. Consort flutes were played mostly in music in the Dorian and related modes, and in the upper part of their range, where their tone was even and pure and blended well with the other flutes in the consort. Consort music was a popular pastime for cultured amateur players as well as for professional musicians.

By the early 17th century flutes more frequently appeared in mixed consort music along with bowed and plucked string instruments. German and Italian sacred music, though not often scored for specific instruments, used flutes in various ways. Motets by Michael Praetorius and others sometimes contrasted groups of different instruments against each other. In other pieces a tenor flute was used to play an inner part, with a violin or cornetto on the upper (cantus) part and viol, trombone, or bassoon playing the lower voices. Modes and hexachords were still an essential part of musical theory at the time.

Solo instrumental music became common at about the same time. It is not clear whether it was played on the same type of instrument used for consort music. Certainly by the late 17th century, special types of flute had been developed to play the new music.

Renaissance music theory did not use scales the way modern theory does. To understand how renaissance musicians played music on a consort of flutes it's important to understand the way they grouped the notes into overlapping patterns of six, called hexachords. The hexachords made fingering different sizes of flute (discant, alto/tenor, and bass) easier, as well as transposing consort music so that it would fit on a set of flutes.

Mixed consorts in Vienna, Florence, England, and Germany sometimes use a D flute on the tenor part together with all sorts of other instruments: viols, lutes, cittern, bandora, harpsichord, muted trombone, viola bastarda, discant fiddle, and dulcian.

Flutes, now sometimes referred to as 'fifes' remain in use with drums in military and ceremonial music of England, Italy, France, and Germany.

Michael Praetorius (Wolfenbüttel) and Heinrich Schütz (Dresden) are among the composers writing pieces for multiple choirs of voices and instruments, sometimes specifying groups of flutes to contrast with viols, trombones, crumhorns, recorders, and other instruments.

Marin Mersenne's Harmonie Universelle (1636) gives a four-part Air as an example of music for a flute consort.

Jacob van Eyck's three-part collection of diminution-variations on popular tunes, Der Fluyten Lust-hof (Amsterdam, 1646), specifies a discant flute in G as an alternative to a recorder at the same pitch.

Philbert Rebillé and René Pignon Descoteaux. the latter known as a fine singer, become famous at the French court for their moving interpretations on the flute of the delicate pastoral songs fashionable at the time.

Flutes begin appearing in French and German opera and chamber music in the 1680s. Jean-Baptiste Lully's opera-ballet Le Triomphe de l'Amour (1681) first specifies Flutes d'Allemagne.

The flute starts to become popular as a solo instrument and to acquire its own repertoire with Michel de Labarre's Pieces pour la flute traversiere avec la basse-continue (1702).

Professional flutists nearly all play oboe as their first instrument. In England they appear before a paying audience in public concerts, alongside players of the violin, oboe, recorder, and keyboard. Their repertoire includes new forms such as solos (sonatas or suites for flute and basso continuo) and concertos. Concerts in France and Germany are still mostly private affairs.

A booming market for instruments and music provides opportunities for makers, composers, teachers, and publishers in England, France, Holland, and Germany.

Michlel Blavet begins a brilliant career as a soloist in Paris (1726).

German musicians discover the transverse flute in the 17-teens. Composers including G.P. Telemann and J.S. Bach contribute works in a distinctive style to the growing repertoire for the flute.

The printing of opera arrangements and other music in easy keys for amateurs increases. Meanwhile Dresden flute virtuosi write challenging music in a range of difficult keys. Flutes become a more regular feature of opera scores, and the Italian operatic style dominates flute music.

Quantz's Essay of a Method of Playing the Flute traversiere, a massive treatise on performance practice, is published in German and French in 1752.

Larger-scale instrumental music such as the symphony becomes fashionable in the mid-18th century. Instrumentalists develop distinctive styles of playing, and groups of music-lovers in various cities provide opportunities for flute soloists to make concert tours.

Solo concertos and chamber works by classical composers including Mozart, J.C. Bach, F. A. Hoffmeister feature the flute. Most professional flutists write their own concertos.

Fife and drum bands are now 'traditional' in German and English military music. They appear in the American Colonies during the Seven Years' (French and Indian) War.

The blind child prodigy Friedrich Ludwig Dülon begins a famous career as a touring virtuoso (1779).

Military woodwind ensembles and orchestras begin featuring flutes more frequently, though not regularly.

François Devienne and Antoine Hugot are among 5 professors of flute at the new Paris Conservatoire.

Dulon and Louis Drouet are famous virtuosos. Touring flutists bring different styles of playing to all parts of Europe. Concertos, fantasies, and variations are popular forms.

Charles Nicholson (1795-1837) moves to London from Liverpool and becomes popular as a soloist 1816-36.

In Vienna, Georg Bayr develops a flute with an extended lower range (1813), probably used in early performances of Beethoven, Kuhlau, Schubert, Weber . . .

Enthusiasm for the flute becomes something like a mania in Europe, particularly in England.

Theobald Boehm (1794-1881) gives up his goldsmith's business to beceome a flute virtuoso. Opens a flute making workshop in 1826.

Symphony orchestras now regularly include flutes as well as a full brass section. String sections become larger, and all instruments are playing louder. But mixed wind bands of the military type are much more common, and provide most of the employment and musical training for professional flutists. Concertos are unknown, and solo performance by flutists becomes rare.

Boehm's ring-key flute is officially adopted at the Brussels Conservatoire. But players in other places, including Fürstenau in Saxony and Tulou, Professor at the Paris Conservatoire, dislike its tone and feel it sounds too much like a trumpet. The first Boehm flutes made in America c1844.

Moritz Fürstenau's pupils at Dresden and Leipzig conservatories play Bach sonatas at examinations. But elsewhere, baroque music is forgotten.

1860: Louis Dorus (1812-96) introduces the Boehm flute at the Paris Conservatoire and Louis Lot (1807-96) becomes its official supplier of flutes. Silver flutes become popular in Paris.

Baptiste Sauvlet serves in Bilse's concert orchestra, Berlin, 1873-76, followed by other French and German Boehm flutists. 1879: Roman Kukala introduces the Boehm flute in Vienna.

Emil Prill (1867-1940) of Berlin takes up the Boehm flute (1882).

Debussy's orchestral tone poem Prélude a l'apres-midi d'un faune gives the flute a new musical personality in 1894 with Georges Barrere (1876-1944) playing its solo flute part.

William S. Haynes (1864-1939) and his brother George making Boehm flutes in Boston (1888).

European and American flutists used many different kinds of instrument during the 19th century. Flutists in Vienna favored a conical-bored flute like that shown at right, with a penetrating tone and often with an extended range down to the violin's G. These instruments were used by amateurs as well as professional soloists and in first performances of symphonies by Beethoven and others.

English flutes, imitating those used by the famous virtuoso Charles Nicholson (below, top), had a range to low C and played best in flat keys such as E flat major. French players such as Jean-Louis Tulou used instruments with smaller fingerholes and a more traditional soft tone (below, middle.) German flutists, led by Anton Bernhard Fuerstenau, preferred types that allowed them the maximum of tonal flexibility and blend in an orchestral wind section (below, bottom). In France and England, new types of flute invented by Theobald Boehm won a few advocates and were soon modified to suit the tastes of players in those countries.

After about 1850 the 'Meyer' flute (right), a blend of the traditional keyed flute and the Viennese type, became the commonest type in Eastern and Central Europe and America. It usually had 12 keys, a body of wood, and toward the end of the century a metal-lined ivory headjoint. But from about 1870 on modified Boehm flutes by French and English makers came into more widespread use, more so in orchestras than in bands.

Recordings of flute-players (the earliest c1890) become more common. A female flutist in Germany records in 1906, but women are still excluided from orchestral positions until after World War 2.

1925: electric microphones,"high fidelity" recording, and radio encourages a few flutists to record extensively.

German amateur musicians become interested in the recorder and the baroque repertoire.

Wayman Carver (Chick Webb band) becomes the first well-known jazz flute specialist (1932). He is followed by many more during the 1950s.

German and English professional flutists begin to adapt to French-style playing with vibrato. The process continues until the 1970s.

The first "Urtext" edition (nothing added to what the composer wrote) of Bach's flute sonatas (1936)

Performances and recordings on baroque flutes become more common in Germany and elsewhere after World War 2.

New music (classical and jazz) begins to specify techniques not part of "proper" flute playing.

1962: Frans Brüggen, the first international star of the recorder and baroque flute, begins recording.

Commentators begin to notice that recordings and rapid travel are making flute-playing, at least in mainstream music, sound more uniform and less individual.

1975: Stephen Preston records the Bach sonatas on a baroque flute. Facsimile editions of baroque music become more common. The baroque flute becomes a familiar sound in performances of 18th-century music.

Folk and historical players are rediscovering and adapting earlier instruments and playing styles.

Various alto and bass flutes are invented, for use in modern music and in flute ensembles. Composers use electronics and percussion more in combination with flute.

Pre-1940 Boehm flutes are no longer used by mainstrem professional flutists, who now nearly all play the same "French model" flute, with in-line, perforated keys, B-foot, Cooper embouchure and Cooper scale. But by the late 1990s, wooden flutes have made a comeback in a new, Cooperized form.

March 1996 Canadian flutist Larry Krantz begins his internet FLUTE list.

Flute makers in Paris, London, and New York manufactured Boehm-system ring-key flutes, which were not patented, from about 1838 onward. The French makers modified the mechanism and tone of the Boehm flute to make it more like the instruments they were accustomed to. A ring-key flute by Rudall & Rose of London is shown here. Boehm did patent the cylindrical flute of 1847 in France and England, licensing its production to Godfroy & Lot in Paris and Rudall & Rose in London. This company, later called Rudall, Carte & Co., built flutes to many designs by English inventors that combined various Boehm features--the cylindrical bore, the fingering, parts of the mechanism--in new ways. The most successful was the 'Carte & Boehm's Systems Combined (1867 Patent)' (shown here), which could be played with almost the same fingering as the old keyed flute, as well as with Boehm's fingering.These were made in wood, ebonite, or silver, and were played in some English orchestras until well after World War 2.

In America, where the Boehm flute was not patented, flutists and makers in New York enthusiastically promoted the Boehm flute, mostly playing instruments by Boehm himself or close copies by local builders. In the 1880s William S. Haynes founded a flute making company and began to copy the French-style metal Boehm flutes owned by players of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Other companies in Boston and Elkhart, Indiana, vigorously promoted their own versions of the same models during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

However some flutists continued to object to aspects of the Boehm flute, particularly its fingering and tone. In Germany a 9- or 11- keyed flute of a pattern introduced by Heinrich Friedrich Meyer of Hamburg in 1853, or a Viennese flute by Koch or Ziegler, remained the usual orchestral instrument through the 19th century. The flutist Maximilian Schwedler of Leipzig developed a keyed conical flute to extend the usefulness of the traditional flute in orchestral music by Richard Strauss and others, while attempting to preserve its traditional sound. These were played in some German ensembles until after World War 1.Schwedler's 'Reform' flute is shown here.

The modern flute descends from inventions made in 1832 and 1847 by the Bavarian goldsmith, flute virtuoso, and industrial designer Theobald Boehm, and modified by many other instrument-makers since then. By the early 20th century and the recording era, French-style metal Boehm flutes had become the commonest type in Europe and America.

During the 1960s flute maker Albert Cooper and a group of English players re-scaled the model to fit a standard pitch of a=440 that had come into worldwide use by about 1950. At the same time Cooper introduced new styles of cutting the flute's embouchure hole, further altering its sound-ideals. Cooper's innovations were adopted by manufacturers in America and Japan, now the only countries with viable flute-making industries.

Despite the dominant position of the Boehm-Lot-Cooper metal flute, changes in design since 1970 have helped the instrument adapt to new musical styles.

History is still going on, so this page will eventually have information about modern developments that are of historic importance. This will include the invention of new key-systems for playing particular kinds of music, the use of electronics in flute music, and the use of new materials and techniques in flute building.