Birds

High-level taxonomy

Birds are categorised as a biological class, Aves. The

earliest known species of this class is Archaeopteryx

lithographica, from the Late Jurassic period. According to

the most recent consensus, Aves and a sister group, the

order Crocodilia, together form a group of unnamed rank, the

Archosauria.

Phylogenetically, Aves is usually defined as all descendants

of the most recent common ancestor of modern birds (or of a

specific modern bird species like Passer domesticus), and

Archaeopteryx. Modern phylogenies place birds in the

dinosaur clade Theropoda.

Modern birds are divided into two superorders, the

Paleognathae (mostly flightless birds like ostriches), and

the wildly diverse Neognathae, containing all other birds.

Bird orders

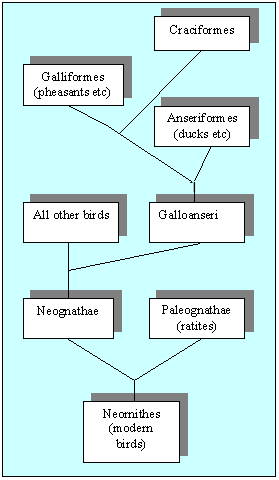

Relationships between bird orders according the

Sibley-Ahlquist taxonomy. "Galloanseri" is now

considered a superorder Galloanserae.

This is a list of the taxonomic orders in the class Aves.

The

list of birds gives a more detailed summary, including

families.

Paleognathae:

- Struthioniformes, Ostrich, emus, kiwis, and allies

Tinamiformes, tinamous

Neognathae:

- Anseriformes, waterfowl

Galliformes, fowl

Gaviiformes, loons

Podicipediformes, grebes

Procellariiformes, albatrosses, petrels, and allies

Sphenisciformes, penguins

Pelecaniformes, pelicans and allies

Ciconiiformes, storks and allies

Phoenicopteriformes, flamingos

Accipitriformes, eagles, hawks and allies

Falconiformes, falcons

Turniciformes, button-quail

Gruiformes, cranes and allies

Charadriiformes, gulls, plovers and allies

Pteroclidiformes, sandgrouse

Columbiformes, doves and pigeons

Psittaciformes, parrots and allies

Cuculiformes, cuckoos, turacos, hoatzin

Strigiformes, owls

Caprimulgiformes, nightjars and allies

Apodiformes, swifts

Trochiliformes, hummingbirds

Coraciiformes, kingfishers

Piciformes, woodpeckers and allies

Trogoniformes, trogons

Coliiformes, mousebirds

Passeriformes, passerines

Note: This is the traditional classification (the

so-called

Clements order). A more recent, radically different

classification based on molecular data has been developed

(the so-called Sibley-Monroe classification or Sibley-Ahlquist

taxonomy). This has influenced taxonomical thinking

considerably, with the Galloanserae proving well-supported

by recent molecular, fossil and anatomical evidence[citation needed].

With increasingly good evidence, it has become possible by

2006 to test the major proposals of the Sibley-Ahlquist

taxonomy. The results are often nothing short of astounding,

see e.g. Charadriiformes or Caprimulgiformes.

Extinct bird orders

A wide variety of bird groups became extinct during the

Mesozoic era and left no modern descendants. These include

the Order Archaeopterygiformes, Order Confuciusornithiformes,

toothed seabirds like the Hesperornithiformes and

Ichthyornithes, and the diverse Subclass Enantiornithes ("opposite birds").

For a complete listing of prehistoric bird groups, see

Fossil birds.

Shoebill, Balaeniceps rex

Evolution

There is

significant evidence that birds evolved from theropod

dinosaurs, specifically, that birds are members of

Maniraptora, a group of theropods which includes

dromaeosaurs and oviraptorids, among others.[1] As more

non-avian theropods that are closely related to birds are

discovered, the formerly clear distinction between non-birds

and birds becomes less so. Recent discoveries in northeast

China (Liaoning Province) demonstrating that many small

theropod dinosaurs had feathers contribute to this

ambiguity.

The basal bird Archaeopteryx, from the Jurassic, is

well-known as one of the first "missing links" to be found

in support of evolution in the late 19th century, though it

is not considered a direct ancestor of modern birds.

Confuciusornis is another early bird; it lived in the Early

Cretaceous. Both may be predated by Protoavis texensis,

though the fragmentary nature of this fossil leaves it open

to considerable doubt if this was a bird ancestor. Other

Mesozoic birds include the Enantiornithes, Yanornis,

Ichthyornis, Gansus and the Hesperornithiformes, a group of flightless divers

resembling

grebes and

loons.

The recently discovered dromaeosaur Cryptovolans was

capable of powered flight, possessed a sternal keel and had

ribs with uncinate processes. In fact, Cryptovolans makes a

better "bird" than Archaeopteryx which is missing some of

these modern bird features. Because of this, some

paleontologists have suggested that dromaeosaurs are actually basal birds whose larger

members are secondarily flightless, i.e. that dromaeosaurs

evolved from birds and not the other way around. Evidence

for this theory is currently inconclusive, but digs continue

to unearth fossils (especially in China) of the strange

feathered dromaeosaurs. At any rate, it is fairly certain

that avian flight existed in the mid-Jurassic and was "tried

out" in several lineages and variants by the mid-Cretaceous.

Snowy Owl, Bubo scandiacus

Although ornithischian (bird-hipped) dinosaurs share the

same hip structure as birds, birds actually originated from

the saurischian (lizard-hipped) dinosaurs (if the

dinosaurian origin theory is correct), and thus arrived at

their hip structure condition independently. In fact, the

bird-like hip structure also developed a third time among a

peculiar group of theropods, the Therizinosauridae.

An alternate theory to the dinosaurian origin of birds,

espoused by a few scientists (most notably Lary Martin and

Alan Feduccia), states that birds (including maniraptoran

"dinosaurs") evolved from early archosaurs like Longisquama,

a theory which is contested by most other scientists in

paleontology, and by experts in feather development and

evolution such as R.O. Prum. See the Longisquama article for more on this alternative.

Modern birds are classified in Neornithes, which are now

known to have evolved into some basic lineages by the end of

the Cretaceous. The Neornithes are split into the

Paleognathae and Neognathae. The paleognaths include the

tinamous (found only in Central and South America) and the

ratites. The ratites are large flightless birds, and include

ostriches, cassowaries, kiwis and emus (though some

scientists suspect that the ratites represent an artificial

grouping of birds which have independently lost the ability

to fly in a number of unrelated lineages). The basal

divergence from the remaining Neognathes was that of the

Galloanseri, the superorder containing the Anseriformes (ducks,

geese and

swans), and the

Galliformes (the

pheasants,

grouse, and their allies). See the chart for more

information.

The classification of birds is a contentious issue.

Sibley & Ahlquist's Phylogeny and Classification of

Birds (1990) is a landmark work on the classification of

birds (although frequently debated and constantly revised).

A preponderance of evidence seems to suggest that the modern

bird orders constitute accurate

taxa. However, scientists are not in agreement as to the

relationships between the orders; evidence from modern bird

anatomy, fossils and DNA have all been brought to bear on

the problem but no strong consensus has emerged. More

recently, new fossil and molecular evidence is providing an

increasingly clear picture of the evolution of modern bird

orders.

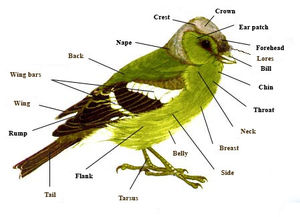

Anatomy of a typical bird

Bird anatomy

-

Birds have a

body plan that shows so many unusual adaptations (mostly

aiding

flight) that birds have earned their own unique class in

the vertebrate phylum.

Nesting

Eggs

All birds lay amniotic eggs[2] with hard shells made

mostly of calcium carbonate. Non-passerines typically have

white eggs, except in some ground-nesting groups such as the

Charadriiformes, sandgrouse and nightjars, where camouflage

is necessary, and some parasitic cuckoos which have to match

the passerine host's egg. Most passerines, in contrast, lay

coloured eggs, even if, like the tits they are hole-nesters.

The brown or red protoporphyrin markings on passerine

eggs reduce brittleness and are a substitute for calcium

when that element is in short supply. The colour of

individual eggs is genetically influenced, and appears to be

inherited through the mother only, suggesting that the gene

responsible for pigmentation is on the sex

determining W chromosome (female birds are WZ, males ZZ).

The eggs are laid in a nest, which may be anything from a

bare cliff ledge or ground scrape to elaboratey decorated

structures such as those of the oropendolas.

Social systems and parental care

The three mating systems that predominate among birds are

polyandry, polygyny, and monogamy. Monogamy is seen in

approximately 91% of all bird species. Polygyny constitutes

2% of all birds and polyandry is seen in less than 1%. Monogamous species of

males and females pair for the breeding season. In some

cases, the individuals may pair for life.

One reason for the high rate of monogamy among birds is

the fact that male birds are just as adept at parental care

as females. In most groups of animals, male parental care is

rare, but in birds it is quite common; in fact, it is more

extensive in birds than in any other vertebrate class. In

birds, male care can be seen as important or essential to

female fitness. "In one form of monogamy such as with

obligate monogamy a female cannot rear a litter without the

aid of a male"

[3].

These

Redwing hatchlings are completely dependent

on parental care.

The parental behavior most closely associated with

monogamy is male

incubation. Interestingly, male incubation is the most

confining male parental behavior. It takes time and also may

require physiological changes that interfere with continued

mating. This extreme loss of mating opportunities leads to a

reduction in reproductive success among incubating males.

"This information then suggests that sexual selection may be

less intense in taxa where males incubate, hypothetically

because males allocate more effort to parental care and less

to mating"

[4]. In other words, in

bird species in which male incubation is common, females

tend to select mates on the basis of parental behaviors

rather than physical appearance.

Birds and humans

Chinstrap Penguin, Pygoscelis antarctica

A

birdbox is an artificial platform for birds

to make a nest

Birds are an important food source for

humans. The most commonly eaten species is the domestic

chicken and its

eggs, although

geese,

pheasants,

turkeys, and

ducks are also widely eaten. Other birds that have been

utilized for food include

emus,

ostriches,

pigeons,

grouse,

quails,

doves,

woodcocks,

songbirds, and others, including small

passerines such as

finches. Birds grown for human consumption are referred

to as

poultry.

At one time

swans and

flamingos were delicacies of the rich and powerful,

although these are generally protected now.

Besides meat and eggs, birds provide other items useful

to humans, including

feathers for bedding and decoration, guano-derived

phosphorus and nitrogen used in fertilizer and gunpowder,

and the central ingredient of bird's nest soup.

Many species have become extinct through over-hunting,

such as the Passenger Pigeon, and many others have become

endangered or extinct through habitat destruction,

deforestation and intensive agriculture being common causes for declines.

Numerous species have come to depend on human activities

for food and are widespread to the point of being pests. For

example, the common pigeon or

Rock Pigeon (Columba livia) thrives in urban

areas around the world. In North America, introduced

House Sparrows, European Starlings, and House Finches are similarly widespread.

Other birds have long been used by humans to perform

tasks. For example,

homing pigeons were used to carry messages before the

advent of modern instant communications methods (many are

still kept for sport).

Falcons are still used for hunting, while

cormorants are employed by fishermen.

Chickens and

pigeons are popular as experimental subjects, and are

often used in biology and comparative psychology research. As birds are very

sensitive to toxins, the

Canary was used in

coal mines to indicate the presence of poisonous gases,

allowing miners sufficient time to escape without injury.

Colorful, particularly tropical, birds (e.g. parrots, and

mynas) are often kept as pets although this practice has led

to the illegal trafficking of some endangered species;

CITES, an international agreement adopted in 1963, has

considerably reduced trafficking in the bird species it

protects.

Bird diseases that can be contracted by humans include

psittacosis, salmonellosis, campylobacteriosis, Newcastle's

disease, mycobacteriosis (avian tuberculosis), avian

influenza, giardiasis, and cryptosporidiosis.

Threats to birds

According to Worldwatch Institute, bird populations are

declining worldwide, with 1,200 species facing extinction in

the next century.

[5] Among the biggest

cited reasons are habitat loss,[6]

predation by nonnative species,[7]

oil spills and pesticide use, hunting and fishing, and

climate change.

Trivia

- To preen or groom their feathers, birds use their

bills to brush away foreign particles.

- The birds of a region are called the

avifauna.

- Few birds use chemical defences against predators.

Tubenoses can eject an unpleasant oil against an

aggressor, and some species of pitohui, found in New

Guinea, secrete a powerful neurotoxin in their skin and feathers.

- The

Latin word for bird is avis.

Fledgling

A juvenile

Laughing Gull

Bird families and

taxonomic discussion are given in

list of birds and

Sibley-Ahlquist taxonomy.

References

- ^

Early Adaptive Radiation of Birds: Evidence from Fossils

from Northeastern China -- Hou et al. 274 (5290): 1164

-- Science. Retrieved on

2006-07-21.

- ^

Education - Senior 1. Manitoba Fisheries Sustainable

Development. Retrieved on

2006-10-09.

- ^

Gowaty, Patricia Adair

(1983). Male Parental Care and Apparent Monogamy among

Eastern Bluebirds (Sialia sialis). The

American Naturalist 121 (2): 149-160.

- ^

Ketterson, Ellen D.,

and Nolan, Val (1994). Male Parental Behavior in Birds.

Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 25:

601-28.

- ^

Worldwatch Paper #165: Winged Messengers: The Decline of

Birds. Retrieved on

2006-07-21.

- ^

Help Migratory Birds Reach Their Destinations.

Retrieved on

2006-07-21.

- ^

Protect Backyard Birds and Wildlife: Keep Pet Cats

Indoors. Retrieved on 2006-07-21.

External links