| Anglerfishes |

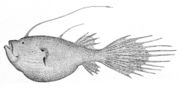

Melanocetidae: humpback anglerfish, Melanocetus

johnsonii

|

|

Scientific classification |

|

|

| Suborders |

Antennarioidei

Lophioidei

Ogcocephalioidei

See text for families. |

Anglerfishes are bony fishes in the

order Lophiiformes.[1]

An anglerfish has a head of enormous size, broad, flat

and depressed, with the remainder of the body appearing

merely like an appendage. Anglerfish may grow to a length of

200 cm (6.5 feet); specimens of 90 cm (3 ft.) are common.

It's maximum weight is 30 kilos (1000 US ounces)

Monkfish in natural envorinment

Anglerfishes are, for the most part, deep-sea fishes,

though there are some families that have shallow-water

representatives, including one, the frogfishes (family

Antennariidae), that occurs only in shallow water. Examples

of other anglerfish families that have some shallow water

species are the goosefishes (family Lophiidae) and the

batfishes (family Ogcocephalidae). These families also have

deep water representatives. The deep-sea mid-water

anglerfishes belong to the superfamily Ceratioidea.

The order was formerly known as Pediculati.

Predation

Anglerfishes are named for their characteristic method of

predation, Angler being another word for fisherman. The anglerfish

has three long filaments sprouting from the middle of its

head; these are the detached and modified three first spines

of the anterior dorsal fin. As with all anglerfish species,

the longest filament is the first (the illicium). This first

spine protudes above the fish's eyes, and terminates in an

irregular growth of flesh (the esca) at the tip of the

spine. The spine is movable in all directions, and the esca

can be wiggled so as to resemble a prey animal, and thus to

act as bait to lure other predators close enough for the

anglerfish to devour them whole. The jaws are triggered in

automatic reflex by contact with the tentacle. (The netdevil

anglerfish has similar growths protruding from its chin as

well.)

As most anglerfish live mainly in the oceans' aphotic

zones, where the water is too deep for sunlight to

penetrate, their predation relies on the "lure" being

bioluminescent (via bacterial symbiosis). In a related adaptation, anglerfish are dull

gray, dark brown or black, and are thus not visible either

in their own light or in that of similarly luminescent prey.[2]

The wide mouth extends all around the anterior

circumference of the head, and both jaws are armed with

bands of long pointed teeth, which are inclined inwards, and

can be depressed so as to offer no impediment to an object

gliding towards the stomach, but to prevent its escape from

the mouth. The anglerfish is able to distend both its jaw

and its stomach (its bones are thin and flexible) to

enormous size, allowing it to swallow prey up to twice as

large as its entire body.

Some benthic (bottom-dwelling) forms have arm-like

pectoral fins which the fish use to walk along the ocean

floor. The pectoral and ventral fins are so articulated as

to perform the functions of feet, the fish being enabled to

move, or rather to walk, on the bottom of the sea, where it

generally hides itself in the sand or amongst sea-weed. All

around its head and also along the body the skin bears

fringed appendages resembling short fronds of sea-weed, a

structure which, combined with the extraordinary faculty of

assimilating the colour of the body to its surroundings,

assists this fish greatly in concealing itself in places

which it selects on account of the abundance of prey.

Reproduction

Linophrynidae: A 46 mm female Photocorynus

spiniceps with male

attached to its back. The adult males of this

species, less than 1 cm long, are among the

smallest adult vertebrates.

Antennariidae: striated frogfish, Antennarius striatus

Linophrynidae: Haplophryne mollis

Chaunacidae: pink frogmouth, Chaunax pictus: B.K.

Phillips

Ceratiidae: Krřyer's deep sea angler fish, Ceratias

holboelli

Some anglerfish have a unique mating method. Since

individuals are rare and encounters doubly so, finding a

mate is a problem, especially at a time when both

individuals are ready to spawn. When scientists first

started capturing ceratioid anglerfish, they noticed that

all of the specimens were females. These individuals were a

few inches in size and almost all of them had what appeared

to be

parasites attached to them. It turned out that these

"parasites" were the remains of male ceratioids.

When a male of one of these species hatches, it is

equipped with extremely well developed

olfactory organs that detect scents in the water. They have

no digestive system, and thus are unable to feed

independently. They must find a female anglerfish, and

quickly, or else they will die. The sensitive olfactory

organs help him to detect the pheromones that signal the

proximity of a female anglerfish. When he finds a female, he

bites into her flank, and releases an enzyme which digests

the skin of his mouth and her body, fusing the pair down to

the blood vessel level. The male then atrophies into nothing

more than a pair of gonads that release sperm in response to

hormones in the female's bloodstream indicating egg release.

This is an extreme example of sexual dimorphism. However, it ensures that when the

female is ready to spawn, she has a mate immediately

available.[2]

The spawn of the angler is very remarkable. It consists

of a thin sheet of transparent gelatinous material 2 or 3

ft. broad and 25 to 30 ft. in length. The eggs in this sheet

are in a single layer, each in its own little cavity. The

spawn is free in the sea. The larvae are free-swimming and

have the pelvic fins elongated into filaments.

Consumption

In Europe, the tail meat is widely used in cooking and is

often compared to lobster tail in taste and texture. It is

therefore sometimes referred to as "poor man's lobster." The

anglerfish is a culinary speciality in certain Asian

countries. In Japan each fish sells for as much as USD$150.

The liver alone, considered a great delicacy, can cost

USD$100.

References

-

^

"Lophiiformes".

FishBase. Ed. Ranier Froese and Daniel Pauly.

February 2006 version. N.p.: FishBase, 2006.

- ^

a b

Ramsey Doran.

Deep sea anglerfish. Retrieved on 3 April 2006.

This article incorporates text from the

Encyclopćdia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a

publication now in the

public domain.